A Step Back to Level Up

I took time off from work to deepen my web dev and engineering skills, explore new technologies, and build personal projects—all with the goal of becoming a more competent, well-rounded engineer.

Project: My Website (1st Iteration)

I originally planned to maintain the site with discipline—writing regularly about web development and software engineering. But that turned out to be a lot harder than I expected. After a few posts, I abandoned the writing routine (and the website itself) and moved on to other things. Still, it was a good exercise in setting up a project from scratch and getting my thoughts out in public, even briefly.

Along the way, I also spent time researching the MDX and unified plugin ecosystem—exploring how to enhance the rendering of content blocks like syntax-highlighted code snippets, custom components, and more. That experience gave me a much clearer understanding of how MDX content is parsed, transformed, and rendered on the web.

Project: Website Redesign for My Cousin

One of my cousins wanted to redesign the website for the university lab he was running (originally built with Wix), so I built him a brand-new site with a cleaner design, using Next.js 13 and Tailwind CSS.

This wasn’t a commercial or paid project—it came from goodwill, and from my own curiosity to tinker with the new App Router and React Server Components (RSC) introduced in Next.js 13.

Looking back, I didn’t fully understand it at the time, but I did notice that navigation between pages felt noticeably slower than I’d expected. Later, I realized that this was due to the way RSC works: on every navigation, the browser hits the server again to fetch a fresh RSC payload—similar to traditional SSR or SSG sites.

In contrast, earlier versions of Next.js used client-side navigation by default. While that approach requires a heavier initial JS payload, once everything is loaded, transitions between pages feel nearly instantaneous.

This experience helped me understand a nuanced aspect of web performance: RSC can improve initial page load times, but it doesn’t necessarily make subsequent navigations faster. It was a valuable lesson in how architectural choices affect perceived performance on the web.

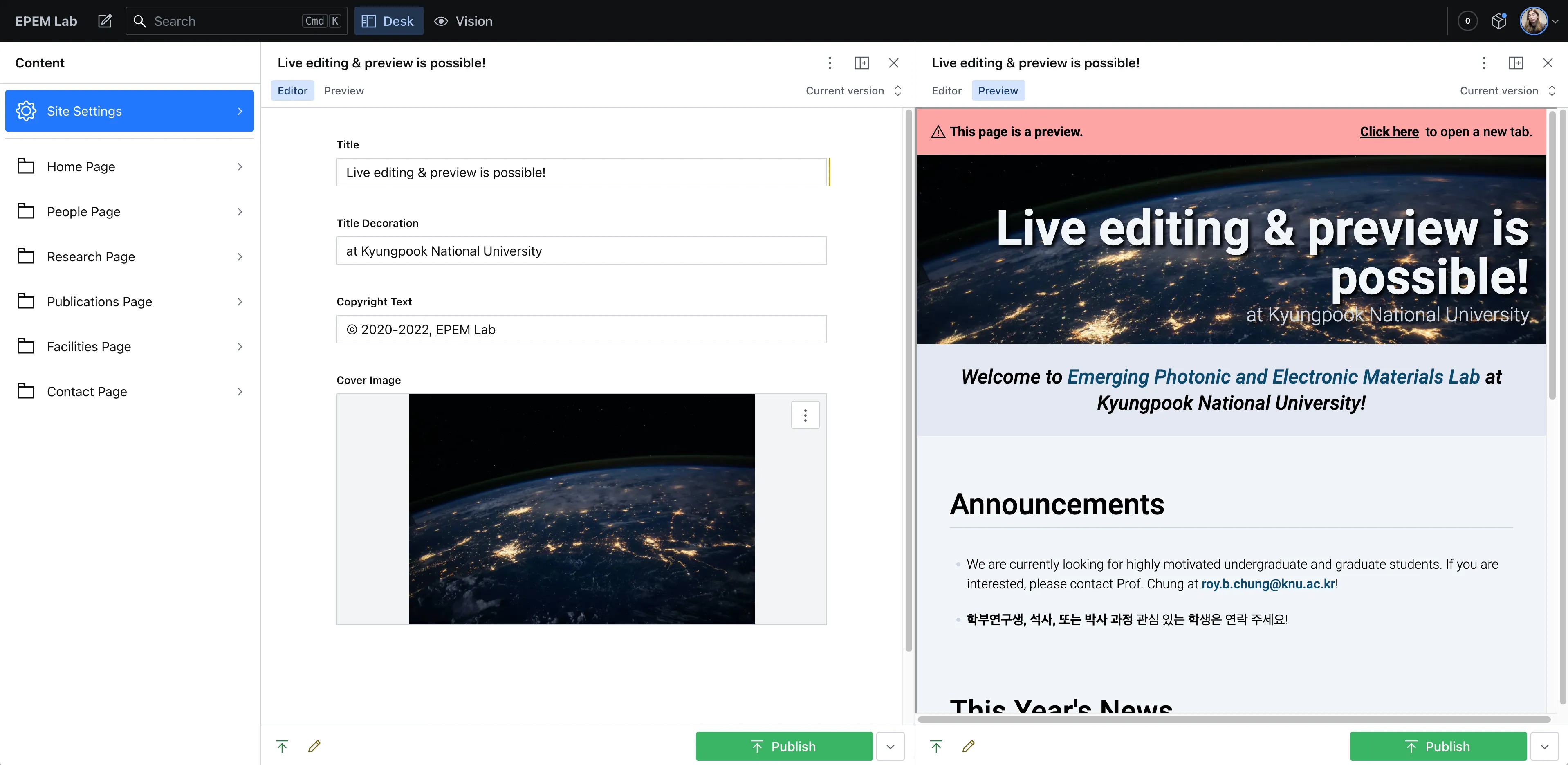

Project: Adding a CMS to My Cousin’s Site

After launching the redesigned site, an obvious limitation emerged: my cousin had to manually edit the source code and push changes to GitHub just to publish new content. It was inconvenient—and clearly not sustainable in the long run.

While researching ways to solve this, I came across the term headless CMS: a content management system that’s decoupled from the presentation layer and serves content via API endpoints.

That was exactly what I needed. After looking around, I settled on Sanity—a headless CMS with strong developer reviews, solid documentation, and a helpful Next.js integration template to get started.

Once I began customizing the template and digging into the docs, I realized just how big a leap it was to go from editing markdown files to using a fully-fledged CMS. I had to:

-

Define structured content using Sanity Schemas

-

Customize the rich text editor with my own formatting shortcuts

-

Learn GROQ — Sanity’s query language

-

Set up preview/publish flows using Next.js API Routes and Sanity Webhooks

I eventually got everything working the way I wanted, but the complexity of it all left me both impressed by what CMSes make possible—and curious if there might be simpler alternatives out there.

Still, I think headless CMSes are incredibly empowering tools for non-technical content creators. I’m looking forward to trying out other options like Strapi in the future.

Experiment: Image Optimization with Sanity

While working with Sanity in the previous project, I discovered that it offers a surprising number of built-in image optimization features—like:

- image dimensions extraction

- low-quality image previews (LQIP)

- responsive images with multiple resolutions

Images are notoriously tricky to optimize for the web, so I was excited to explore what Sanity made possible.

I ended up building a simple image gallery component featuring next/previous buttons and a bottom thumbnail strip. This project eventually became the foundation for many other galleries I’ve built—including the one on this very site.

Experiment: Infinite Scroll Image Gallery

After building my first image gallery, a few new ideas came to mind—so I jumped right into a second experiment. This time, I wanted to explore:

- Infinite scroll for loading more images

- Skeleton loading animations

- Low-quality image previews (LQIP) alongside skeletons

- Slide-show-like animations between image transitions

This was a much more involved project, largely due to:

- The complexity of managing a virtualized list

- Coordinating transitions between the main image and its thumbnails

- Sharing image load states across multiple components

List virtualization is powerful for infinite scrolling—it keeps the DOM tree lean by only rendering visible items. But it’s not without trade-offs:

- Most virtualizers assume consistent item shapes or sizes

- Styling them to match your exact UI can be tricky

- Programmatically scrolling to a specific item can feel imprecise if item heights vary

It’s a great tool—but one that should be adopted with care after weighing its benefits and constraints.

Adding animations to an image gallery adds polish—but coordinating multiple simultaneous animations can easily become overwhelming or distracting.

Some thoughts based on this project:

- If animations aren’t orchestrated, the overall experience can feel chaotic

- Animation libraries like Motion are powerful, but abstract away a lot of complexity

- Until you understand how things work under the hood, it’s often best to stay close to official examples

This project gave me a stronger appreciation for how much thought goes into balancing between interactivity, usability, and performance.

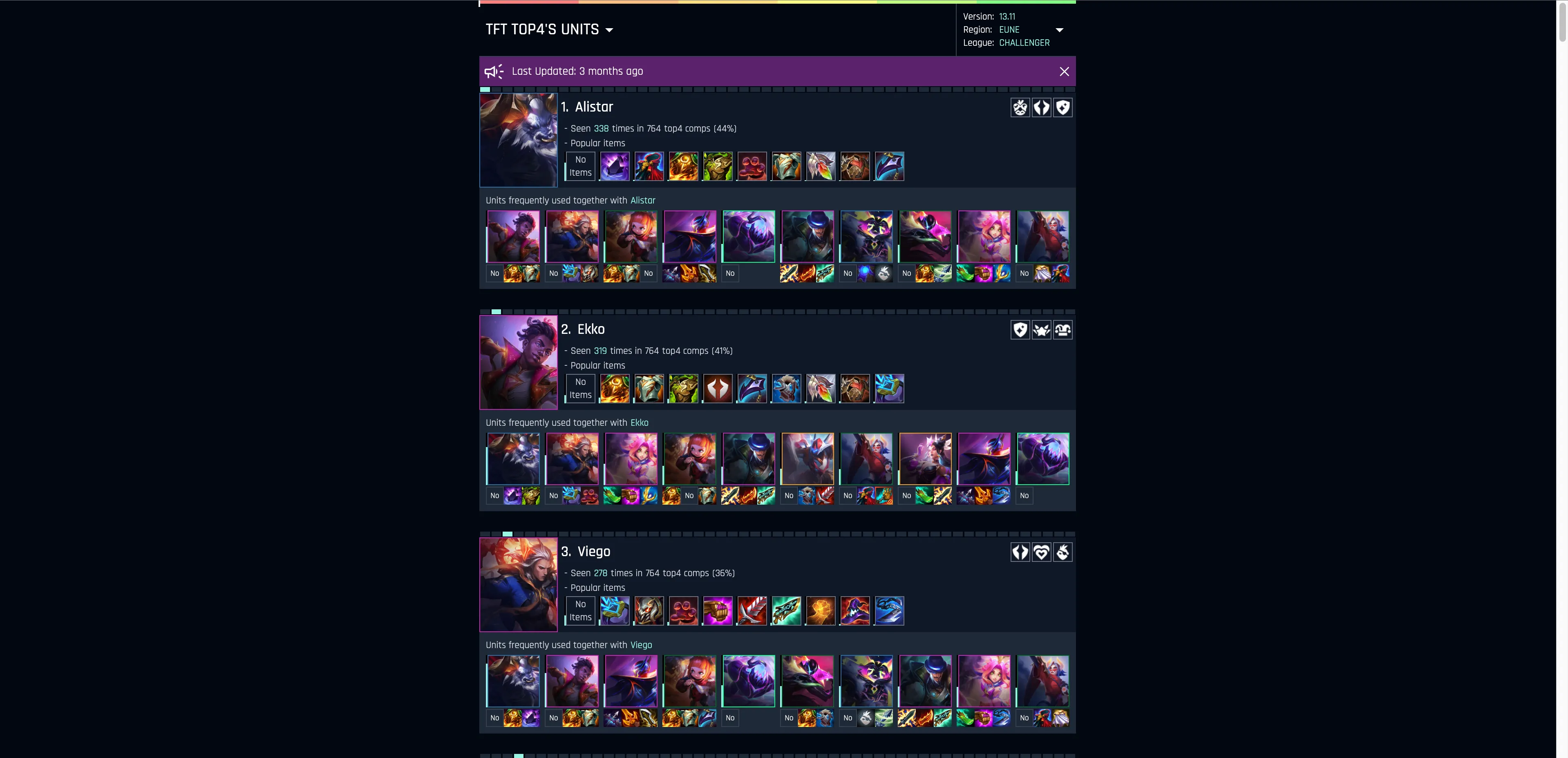

Project: Teamfight Tactics Stats Site

I used to play a game called Teamfight Tactics (TFT) quite a bit—and I was curious if I could build something useful around it using Riot’s public APIs.

In TFT, the meta changes every few months with the release of a new set, and strategies that worked previously become obsolete. That inspired the core idea for this project: analyzing what made players win in the early phase of each new set—looking at things like unit compositions, traits, augments, and items used by the top 4 finishers in each game.

A large portion of this project was spent:

- Understanding Riot’s API responses

- Downloading assets (unit images, icons, etc.) from the CDRAGON API

- Writing Node.js scripts to fetch, parse, and aggregate large datasets

(across versions, regions, leagues, and each category: units, traits, and augments)

I hit blockers—especially around dealing with asset mapping and data processing mostly due to lack of proper documentation—but I pushed through in the end with lots of trial and error.

The main goal was to surface patterns from top-4 finishers:

- Which units appeared most often in winning comps?

- What items were commonly equipped on those units?

- Which other units were frequently paired with them?

This required multi-level aggregation and a lot of data crunching—especially when dealing with item frequency per unit, and unit co-occurrence stats.

On the frontend side, I built a snappy, interactive UI with:

- List virtualization for performance

- Components from Radix UI like

PopoverandDialog - A sprinkle of animations using Motion

I also experimented with static site generation using Next.js’s static export, which let me deploy everything as pre-generated HTML/JS/CSS—no server required.

Open Source: Storybook Contributions

In May 2023, I finally decided to take a proper look at Storybook. I’d seen it mentioned constantly by other developers—some even calling it indispensable for UI component development.

Turns out, they weren’t wrong.

When I first grasped what Storybook actually does—offering an isolated environment to develop and test individual UI components—it felt like I had found a missing piece in my frontend workflow. A place where components can be created, styled, composed, and tested independently from the rest of the app? That just made sense.

What I appreciated most was the separation of concerns it enforced. You could focus purely on UI behavior without worrying about framework quirks, data-fetching, or business logic. This clear separation naturally nudged me toward writing better-structured components.

The discovery was so enlightening that I felt compelled to dig deeper—and ended up making my first meaningful contributions to the project.

What stood out to me the most was how fun and rewarding it was to collaborate with the core maintainers. I’d ask questions when I wasn’t entirely sure about something, and instead of brushing them off, they patiently offered guidance, shared broader context, and gave thoughtful feedback on everything from technical details to project conventions. It felt like having engineering mentors—something I never had during my years working as a frontend developer.

Their encouragement, clear communication, and even the smallest “looks good!” in a pull request review went a long way. That positive feedback loop made me genuinely want to contribute more, and gave me a deeper appreciation for the people behind the tools we rely on every day.

Study: Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP)

As a non-CS major, I’ve always been curious about what computer science students actually study in college. For years, I’d been searching for a way to teach myself the fundamentals, and I kept coming back to this wonderfully curated site called Teach Yourself Computer Science. I must’ve visited it a dozen times, each time promising myself I’d start. That promise finally stuck.

I began with the legendary textbook: Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP). It’s as challenging as everyone says.

I only made it up to section 4.4.3, since the accompanying video lectures from UC Berkeley’s CS 61A ended there—and, admittedly, so did most of my motivation. 😅

To be fair, the core ideas in each chapter weren’t too hard to grasp. But the exercises were tough. Many required background knowledge in math or electrical engineering, and they weren’t something you could just solve after a quick read. Some would take hours (or days) to figure out from scratch.

So I made a pragmatic choice: I mostly read through the solutions (like those at sicp-solutions or SICP Solutions) rather than grinding through each problem myself. It wasn’t ideal, but my goal was more about exposure to foundational ideas than proving I could do all the exercises. I wanted to keep my time focused on learning web technologies.

That said, many of the ideas in SICP felt surprisingly relevant to modern web development, especially React:

- Functional programming: The predictability of pure functions

- Assignment and mutation: And the headaches they cause in concurrent environments

- Delayed evaluation, memoization, thunks—all things that show up in performance tuning and state management

I’d love to return to this book someday with more experience—and a bit more patience.

Project: My Website (2nd Iteration)

It was about time.

After building a few side projects and exploring different web technologies, I felt ready to take another crack at my personal website. Unlike the first version—which I mostly treated as a blog I never really updated—the goal for this second iteration was clear: create a detailed, thoughtful write-up of my professional journey since college, including everything I’d been working on during my sabbatical.

I wanted it finished by the time I started looking for my next job. A place to showcase my projects, reflect on what I’ve learned, and hopefully tell a coherent story about where I’ve been and where I’m going. It took me around two months to build the first “complete” version, but I kept refining features and content well into early 2025.

Writing was just as painful (if not more so) than the actual development. It turns out: trying to write clearly and honestly about past experiences, in a way that makes sense to others, is really hard.

On the implementation side, I reused the image gallery components I had experimented with previously, leaned on Next.js’s static export, and built a solid Storybook workflow. It also became a practical exercise in setting up a monorepo using pnpm workspaces. Knowing from my Storybook contributions that its Next.js support wasn’t as polished as its Vite counterpart, I split out a dedicated package for a Vite-powered Storybook setup—allowing me to develop components in isolation with fewer headaches.

As the number of images on the site grew, bundling them in source control became increasingly unwieldy. I ended up setting up Cloudflare R2 for image hosting—it was simple, fast, and essentially free for a small, low-traffic site like mine.

Personal websites are something I’ve always admired. In fact, they’re part of the reason I wanted to become a web developer in the first place. There’s just something deeply satisfying about having a tiny corner of the internet that you fully control—from the design to the content to the interactivity. I still think that’s one of the coolest things the web allows us to do. 😎

Open Source: React Aria Contributions

I’ve always appreciated a well-crafted UI component library—creating one that gracefully handles browser quirks, device inputs, and accessibility concerns is no small feat. So when I came across React Aria, I was instantly hooked and wanted to learn how it worked under the hood. That curiosity led me to contribute a little to this amazing project.

Web accessibility has long been a sore spot for me. I know it’s important—essential, even—but building it right is hard. Turning best practices from WAI-ARIA into robust components takes a lot of time and care. And let’s face it: most deadlines don’t leave much room to build for users of assistive technologies. Even when you do have time, how many teams have the resources to test across screen readers and other tools?

React Aria gave me a glimpse into that world. Just like we have browser inconsistencies, there are quirks between different assistive technologies (AT) too. Each screen reader or AT behaves a little differently, which adds a whole new layer of complexity.

That’s why libraries like React Aria are so valuable. It’s backed by Adobe, who dogfoods the library through their own apps, and they have the resources to test it thoroughly across ATs. The team behind it—including Devon Govett, creator of Parcel—is incredibly talented, thoughtful, and open to contributions. Every interaction I’ve had with the core maintainers has been professional, thoughtful, and inspiring.

There’s also something cathartic about reading through issues created by fellow developers—trying to reproduce their problems, understand the root cause, and either fix them or come up with a sensible workaround. It’s like helping a stranger untangle a knot you’ve seen before.

Open source contributions can be intimidating—and yeah, sometimes they are. But they’re also deeply rewarding. You get to learn from some of the most experienced engineers in the industry while giving back to a community you care about.

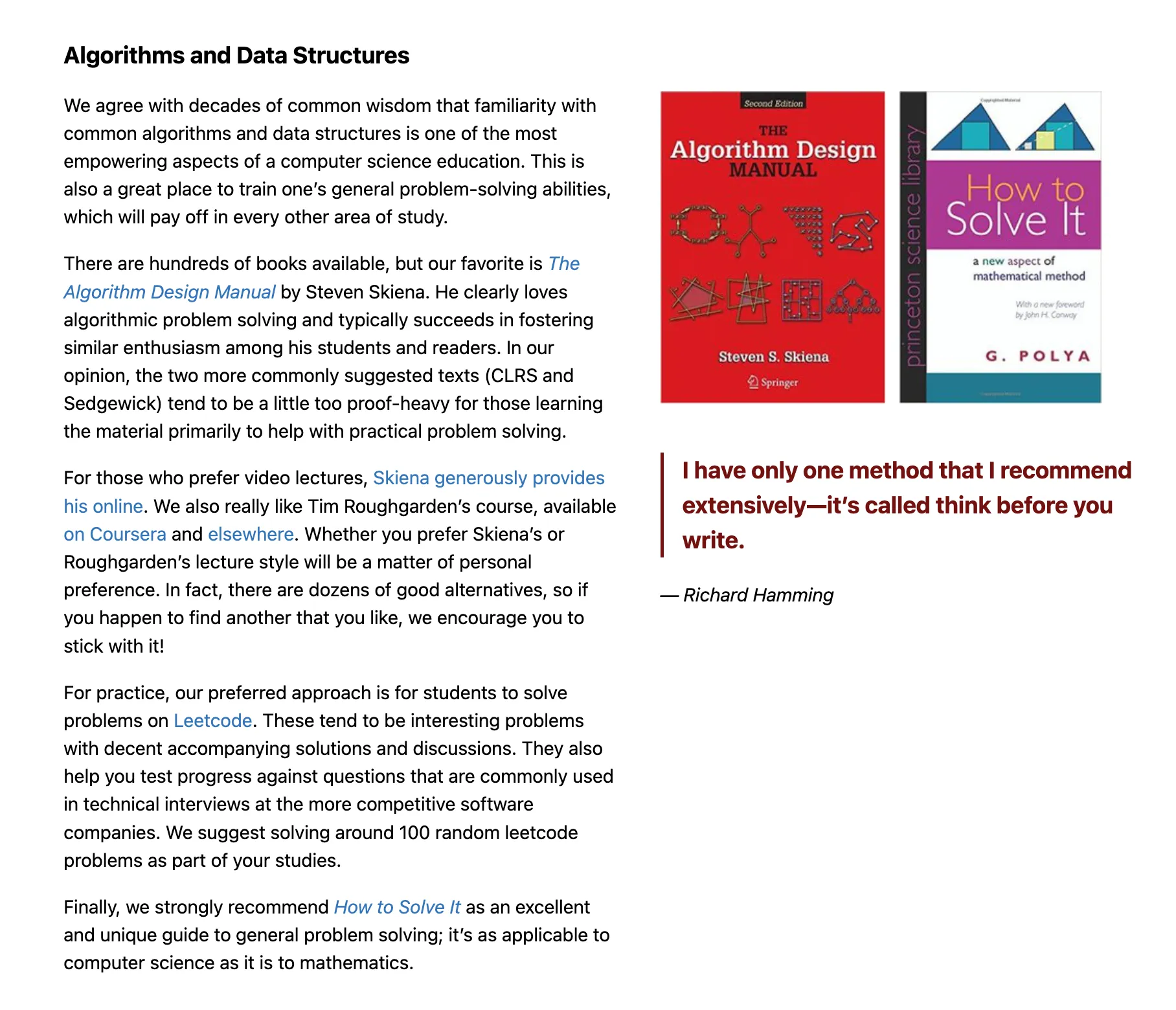

Study: Data Structures and Algorithms

I was hesitant at first. The idea of learning data structures and algorithms “the proper way,” as outlined in Teach Yourself Computer Science, seemed like a serious time commitment—and frankly, a bit intimidating.

But eventually, I bit the bullet. I figured I’d be doing some LeetCode grinding as part of job prep anyway, so I might as well take the time to build a solid foundation along the way.

I began with Skiena’s The Algorithm Design Manual and the accompanying video lectures, but I switched tracks just before the graph algorithms section. I ended up preferring Sedgewick’s textbook and his Coursera courses—Part 1 and Part 2—and stuck with those instead.

What I appreciated most about Sedgewick’s materials was how every algorithm was paired with concrete Java implementations. For me, seeing the concepts and code side by side made everything click more easily. I also liked how the book took time to explain Java fundamentals early on. That made a big difference for someone like me who wasn’t very familiar with the language, especially when it came time to submit assignments.

The hardest part, hands down, was understanding the theory behind performance analysis—order of growth, mathematical proofs, and especially some of the advanced graph and string algorithms.

I won’t pretend I absorbed it all—truth be told, a lot of it is already slipping from memory. But I’m glad I pushed through and studied the subject at least once. It gave me a better appreciation for the underlying mechanics of the code I write, and it made me feel more grounded as an engineer.

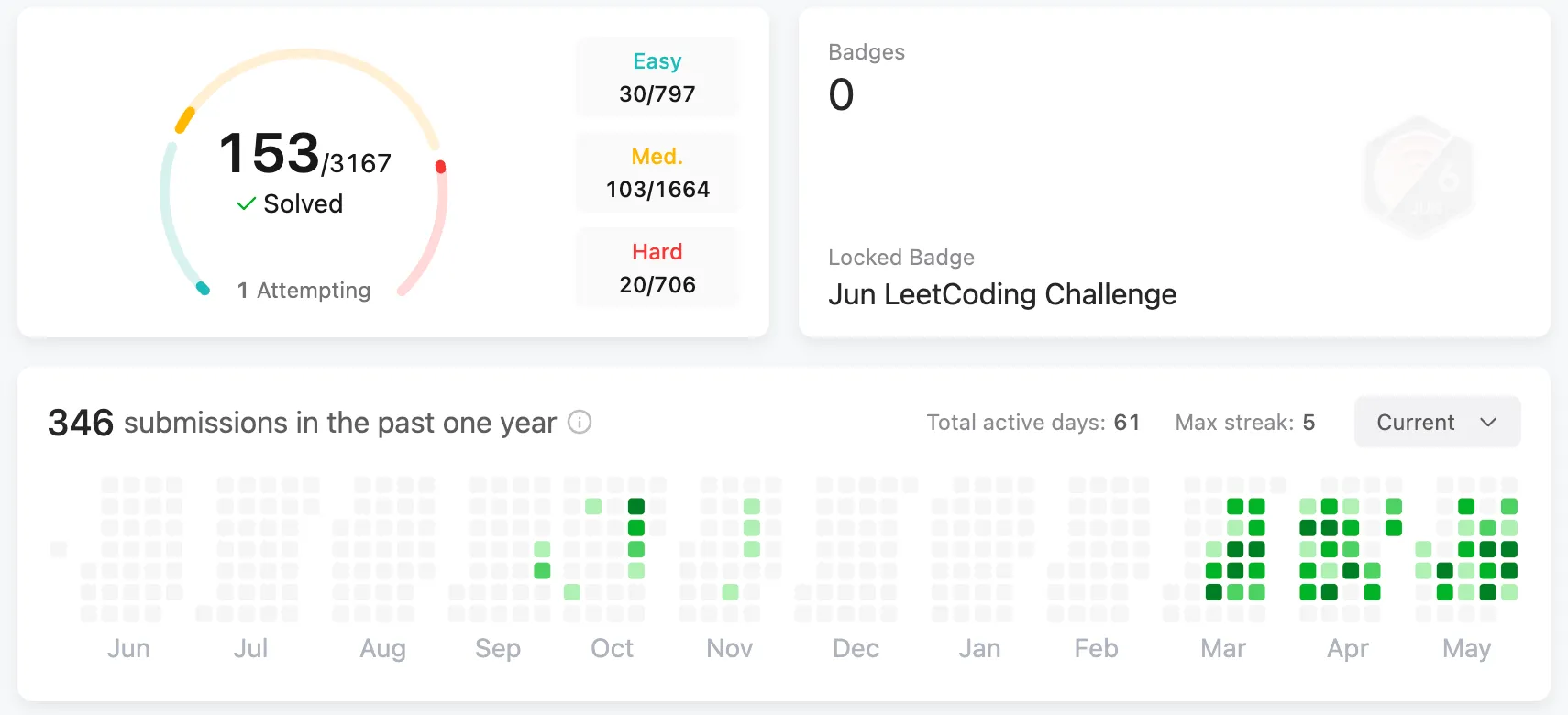

Practice: LeetCode Problem Solving

Eventually, it was time to confront LeetCode again—this time, with a bit more confidence. I had just completed my first serious deep dive into data structures and algorithms (DSA), so I felt better prepared than ever before.

For this round, I followed a thoughtfully curated list of 150 problems known as NeetCode 150. It was a great way to put what I had just learned into practice through real implementations of classic algorithms and patterns.

I won’t pretend I loved solving LeetCode problems (even post-DSA study), but overall it was a worthwhile experience. It helped reinforce many of the concepts I had just encountered—and it gave me a clearer sense of how those ideas are converted to actual code.

While going through the list, I also realized there were a few important concepts I hadn’t touched in my initial DSA study—most notably backtracking and dynamic programming. So I circled back to study those topics using Skiena’s book (for both) and CLRS (for dynamic programming and greedy algorithms). Oddly enough, Sedgewick’s book—which had been my primary learning resource—doesn’t cover these topics at all 🤷♂️.

At some point in the future, I’d like to revisit NeetCode 150 and go through the problems again—partly to strengthen my understanding, and partly just to get faster and more fluent with the patterns.

Study: Designing Data-Intensive Applications

As I was planning to wrap up my sabbatical and start preparing for the job search, I wanted to study one more subject from Teach Yourself Computer Science—and I picked up Designing Data-Intensive Applications (DDIA) to read.

Distributed systems like Hadoop and Spark had always fascinated me—even back when I was working as a data analyst. In fact, I once went out of my way to build a mini Hadoop cluster as a side project back in 2018. So I was genuinely excited to dive into this book.

Overall, I’d say the author did a fantastic job explaining the big ideas behind distributed systems—strategies like replication and partitioning, and the many things that can go wrong when building and operating these systems at scale. In that sense, it’s remarkable that these incredibly complex systems are not just theoretical, but actually power real products used by millions of people with minimal downtime.

I also learned a lot about the inner workings of traditional relational databases—things like indexes, transactions, and how data is physically stored on disk. Reading this made me wish I had encountered the book earlier in my career. It even helped me better understand concepts like OLAP and data warehouses, which I had often heard back in my data analyst days but only vaguely understood.

I’m not sure whether I’ll ever get to work with distributed systems at a massive scale as a frontend developer, but I still think there’s a lot of value in understanding the “invisible” backend infrastructure that powers the software we use every day.

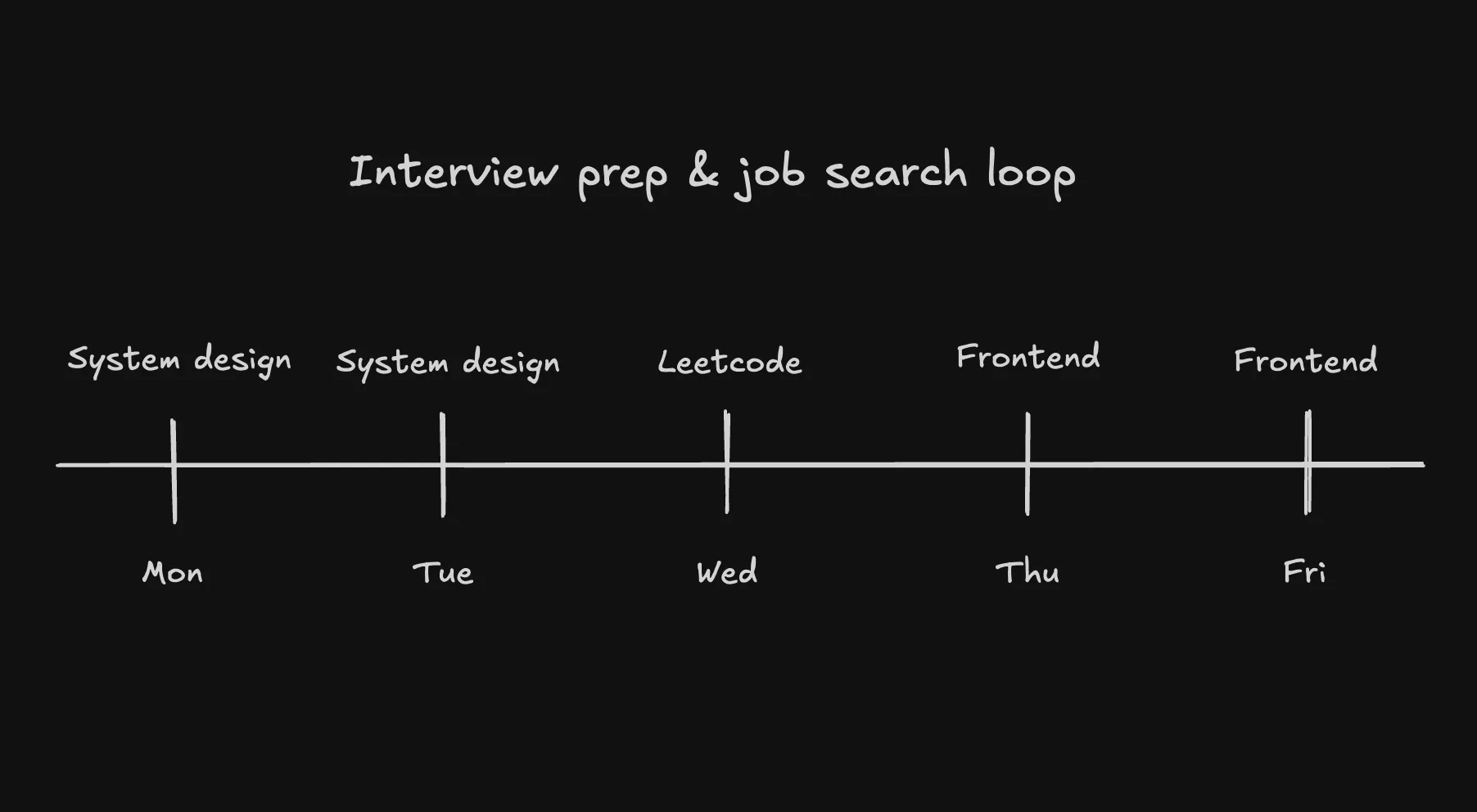

Wrap-up: Interview Prep & Job Search

While I’ve more or less given up on applying to FAANG—or really, any U.S. tech company—due to visa constraints and the fact that I’m currently living outside the States, I still thought it would be a good idea to go through some FAANG-style interview prep while exploring opportunities in the local market.

In particular, I found studying system design to be incredibly helpful—not just for interviews, but also for building a broader understanding of modern software architecture. Knowing what kinds of technologies are out there, when to use them, and what tradeoffs they come with—even at a high level—is valuable for any software engineer. No wonder there’s such heavy emphasis on system design in technical interviews. As for resources, I found Hello Interview to be a great site. Revisiting DDIA was also incredibly useful for this purpose.

To keep my algorithmic skills sharp, I’ve been dedicating one day a week to LeetCode practice. And to not forget my identity as a frontend developer, I’ve set aside two days a week for frontend-specific work—currently going through resources on GreatFrontEnd, with plans to explore other frameworks and libraries soon.

This marks the end of my first (of possibly more to come) sabbatical, and I’m glad to have come out of it with a stronger foundation. That’s exactly what I hope to gain from taking career breaks—because, let’s face it, there’s rarely time for deep learning in most work environments. More often than not, you have to settle for shallow, surface-level knowledge just to keep up with deadlines.

This two-year sabbatical was a bit of an experiment: I wanted to see whether I could maintain the discipline to follow a long-term learning plan, and whether I could stay curious and motivated without the external structure of a job. And honestly, I think I did pretty well. I learned a lot, built some cool stuff, and even made a few open source contributions along the way.

So until the next sabbatical—peace out! ✌️